This Sunday marks the 70th anniversary of the 1945 General Election. The election is widely understood as a significant turning point in modern British history. Labour won their first ever majority government and introduced a wide-ranging programme of social and economic reform, including the inception of NHS exactly three years later, and establishing the foundation of a political consensus that was sustained until the 1970s. Yet the meaning of the election has been contested by historians ever since.

For some, the 1945 election represented the beginning of a golden age for British politics. By comparison to the present period, turnout was high and support for the two main parties was high. It was estimated that 45 per cent of the public listened to election broadcasts on the radio and large numbers flocked to outdoor meetings to see politicians in the flesh(see Lawrence). Labour’s first parliamentary majority represented the highpoint of post-war enthusiasm and consensus for social democracy. The ‘people’s war’ produced a sense of national purpose and social reconciliation through events including conscription, evacuation, rationing and communal air-raid shelters. Labour’s victory was a consequence of greater public engagement and support for collectivism, planning and egalitarianism (see Field).

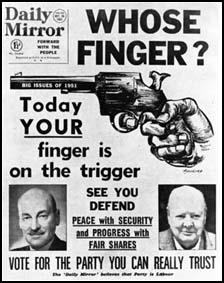

For others, the election has been remembered with greater enthusiasm than was present at the time. Politicians such as Hugh Gaitskell, Herbert Morrison and Harold MacMillan all remarked on the public’s lack of interest in the election. A 1944 Gallup poll showed 36 per cent of the population believed politicians placed their own interests ahead of country. Labour’s victory was the result of anti-Conservative feeling. The ‘spirit of 1945 was a myth’ and few people voted for Labour because they desired socialism or social democracy. Citizens supported the implementation of the 1942 Beveridge report out of individual self-interest and were indifferent to ambitious projects of social transformation. The majority of voters were disengaged from the political process and cynical about the motives of politicians (see Fielding).

Our current research project draws on survey/poll data and volunteer writing in the Mass Observation Archive to offer a new interpretation of this election from the perspective of ordinary people. It is important that we revisit the past to understand political attitudes in the present. Much has been written about the rise of anti-politics in recent years, which presumes a historical narrative that citizens have become increasingly disenchanted from politics, without understanding how citizens engaged with formal politics in the past. Crucially, we revisit 1945 not to answer questions about why Labour won that election, but to explain how citizens understood, imagined and evaluated politics in their everyday lives, and to identify how this has changed in the last 70 years.

Our early findings illustrate that citizens encountered politics and politicians in 1945 primarily by listening to long, uninterrupted speeches on the radio, and by attending local political meetings. These relatively unmediated forms of political interaction could expose politicians who lacked character or had little to say. They also provided an opportunity for politicians to impress with their oratory, authenticity and ability deal with rowdy crowds. Citizens judged politicians on their sincerity, charm, policies and programmes.

We also find that citizens commonly understood party politics as unnecessary. Politics involved ‘mud-slinging’ and ‘axe-grinding’, and was something to be avoided. Many did not want the election to take place and wished that coalition politics would continue after the war. Many expressed preference for independent candidates who demonstrated the ability to rise above the ‘petty squabbling’ of party politics.

So how should we remember the 1945 election today? Maybe this was not a golden period for democratic engagement in that negativity towards formal politics was certainly present. Politicians were frequently conceptualised as ‘gift-of-the–gabbers’ and ‘gas–bags’. Yet we should not mistake cynicism for apathy. Remembering the 1945 election, we should think about the everyday rituals of political interaction that permitted citizens to criticise, but also appreciate some politicians’ character and capacity to make effective collective decisions on their behalf. Returning to the present, we should consider how political interaction has changed over the last 70 years, and examine how this has influenced ordinary people’s decisions about participation in formal politics.