Democratic engagement in the immediate post-war period is sometimes understood as a paradox. Record high levels of voter turn-out, party membership, and support for the two main parties mean the period can be described as a highpoint of political participation. However, evidence of cynicism, self-interest and anti-party feeling has led revisionist historians to characterise citizens as apathetic and disengaged. We believe that volunteer writing in the Mass Observation Archive makes visible how this apparent contradiction between attitudes and behaviour made sense to citizens at the time.

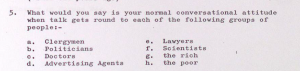

Between 1945 and 1950, Mass Observation asked its panel of volunteer writers to record their engagements, thoughts, and feelings about politics on 22 separate occasions. Open-ended directives asked for panellists’ views on elections, political parties, politicians, and local councils.

We are currently analysing responses to these directives with the aim of identifying the cultural resources MO panellists used to construct understandings, expectations, and judgements of democracy in the immediate post-war period. So far, we have identified three main stories panellists drew upon when writing about politics.

The first shared story we identified was that democracy was important. Duty was a norm mobilised in panellists’ writing. A panellist explained ‘There seems to be a general feeling (justified I think) that it is one’s duty to vote’.(1) Dutiful citizens distinguished themselves from the apathetic masses. Another panellist regarded ‘municipal Elections as very important indeed’, and had ‘been heard to go on record as disapproving of those who take no interest in them’. (2) A consequence of this widely shared story about democracy being important was that some respondents felt guilty about their lack of knowledge, interest, or participation in politics.

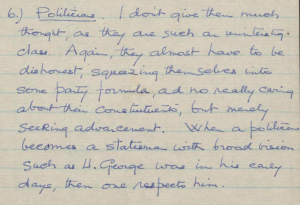

The second narrative emphasised that politicians were flawed. As a class or profession, politicians were described as ‘twisters’, ‘talkers’, ‘clever rogues’, ‘liars’, ‘unscientific’, ‘hypocritical’, and ‘distrusted’. They were repeatedly described as self-seeking and not straight-talking, or in the words of this panellist: ‘out to feather their own nests and gas-bags’.(3) Another panellist suggested ‘we have some gift-o-the-gabbers too’.(4) The ‘gas-bag’, ‘gift-of-the-gabber’ and ‘self-seeker’ were characters who frequently populate the panellists writing about politicians. (We have written more about this here in a working paper).

The third narrative we find is that politics is unnecessary. Throughout the MO material, politics – and party politics in particular – is repeatedly dismissed as ‘a dirty business’, ‘a game’, ‘clap-trap’, ‘eyewash’, ‘platform talk’, ‘guttersnipe’, ‘petty squabbles’, and ‘mud-slinging’. Mud-slinging’ was the most common line in the story circulating in the late 1940s about politics being unnecessary. One panellist was ‘sure this mud-slinging is not liked and gives people a bad view of politics’.(5)

Underpinning this narrative about politics being unnecessary was a storyline that government was best done by those capable of working in what was perceived to be a singular local or national interest. Characters populating this last line included national governments, coalition governments, independents and statesmen. For example, one panellist wrote in their 1945 election diary ‘I am normally non-party, and prefer an independent, or one will stand for a coalition’.(6) In this view, democracy would function more effectively should politicians possess the ability and character to recognise common interests and put them ahead of party interests. As one respondent put it: ‘A statesmen must put the real need of his country first […] A really great man recognises universal greatness and has universal aims’.(7)

We’re currently thinking about these findings in relation to literatures on partisan dealignment, the decline of deference, stealth democracy and other folk theories. Any thoughts on how to proceed would be very welcome.

(1) SxMOA1/3/88, 2514, 28, M, Statistician, North West, 1945.

(2) SxMOA1/3/88, 1210, 28, M, Bank Clerk, South West, 1945.

(3) SxMOA1/3/84, 3545, 28, F, Clerk, Scotland, 1945.

(4) SxMOA1/3/84, 1016, 58, F, Teacher, North East, 1945.

(5) SxMOA1/3/86, 1165, 34, M, Electrical Engineer, South East, 1945.

(6) SxMOA1/3/86, 3388, 54, F, Housewife, South East, 1945.

(7) SxMOA1/3/86, 3648, N/A, F, Weaver, Yorkshire, 1945.