We’re currently at the stage of the project where we’re analysing the material we’ve collected from the Mass Observation Archive. One of the things we’ve been doing is comparing the election diaries of volunteer writers in 1945 and 2001, to see if they can shed light on why anti-political feeling and associated action grew in scope and intensity during the second half of the twentieth century (which we think we can demonstrate using other data collected for the project).

1945

Around the 1945 General Election, MO panellists wrote of encountering politicians via long radio speeches (of 30 minutes or more). They listened to and heard politicians. They discussed speeches with family, friends, and colleagues.

They also wrote of encountering politicians via local political meetings. They attended meetings outside pubs, at the local works, on greens, squares, and market places, and in schools, Co-op halls, town halls, gardens, village rooms, and ambulance halls.

These contexts afforded certain modes of political interaction. They allowed for the testing of politicians, for politicians to demonstrate virtues (and vices), and for citizens to know, judge, and distinguish politicians.

Long radio speeches gave speakers enough rope from which to hang themselves. Delivery had to be lively and interesting. Material had to describe a well-knit argument and a programme for government. Over the course of these speeches, politicians could demonstrate their character (or lack of character).

Political meetings were still more of a test. They were participatory for citizens, who would listen, laugh, applaud, ask questions, donate money. They were often rowdy and citizens would also moan, boo, jeer, heckle, shout, and howl. Politicians were challenged at these meetings. Citizens would ask questions, express their views, and fight among themselves. Some politicians were able to pass the test and one prototypical character of the time was ‘the good speaker’ who communicated policy, demonstrated fight, intelligence, authenticity, and reason, and answered questions – all in a ‘pleasant voice’.

Citizens were able to distinguish between good and bad speakers, and to be impressed by good speakers. They were able to describe politicians in comparative and superlative terms: good and bad speakers, but also better and worse speeches, and best candidates (to be supported).

2001

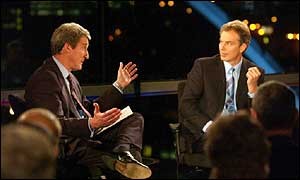

Around the 2001 General Election, MO panellists wrote of encountering politicians via televised debates between politicians or between politicians and journalists. They described these debates as stage-managed affairs where politicians avoided answering questions or addressing topics of concern to voters.

They also wrote of encountering politicians via media coverage of prediction polling and expert opinion. For many panellists, this made the election ‘a foregone conclusion’.

The prototypical category of ‘the good speaker’ did not really exist in 2001. There were fewer characterisations and judgements of individual politicians throughout the diaries of that year. If comparable figures did exist, they were ‘the fraud’ (media savvy, smarmy, slimy, image conscious) and ‘the buffoon’ (mad, insane, pathetic, puerile).

Panellists in 2001 were not very impressed by politicians. They struggled to describe them using positive adjectives; to describe their virtues. And they struggled to describe them using comparative or superlative adjectives; to distinguish better from worse politicians, and to identify the best politicians (worthy of support).

We’re currently thinking about these findings in relation to literatures on videomalaise, media effects, the modernisation of political campaigning, mediatisation, political communication, and political interaction. Any thoughts on how to proceed would be very welcome.